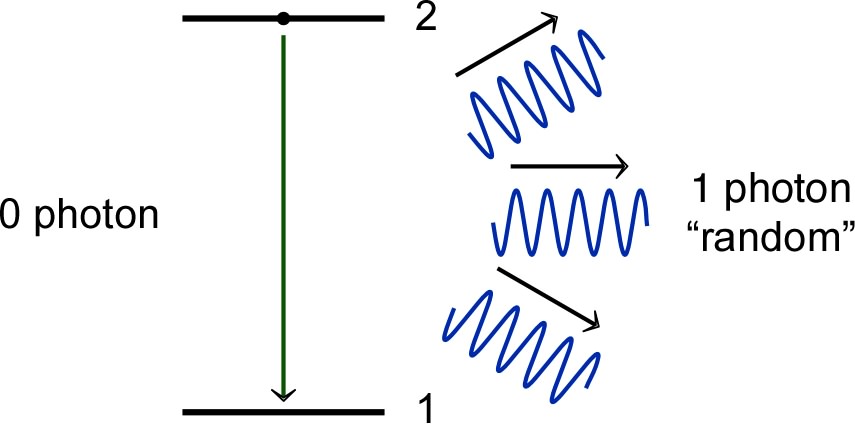

spontaneous emission reveals a photon, emitted with “random” direction and phase

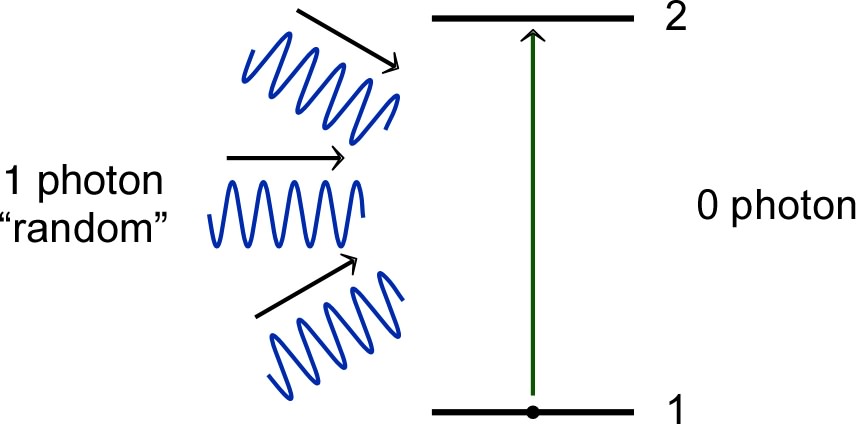

spontaneous absorption removes a photon, absorbed with “random” direction and phase

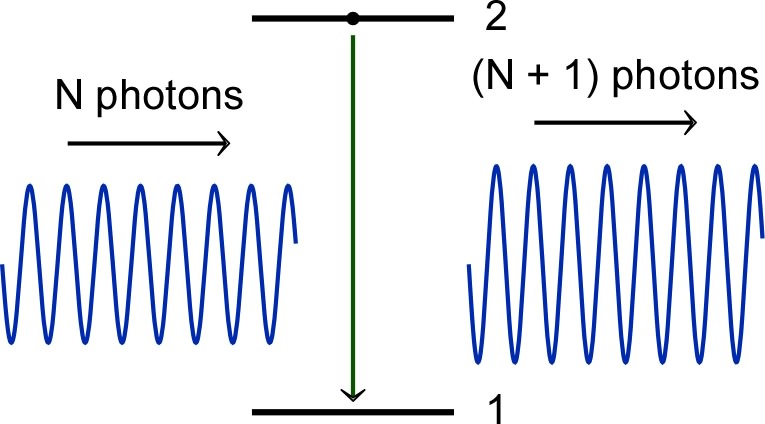

induced emission produces a photon in the same mode that the incident wave (the emission is amplified)

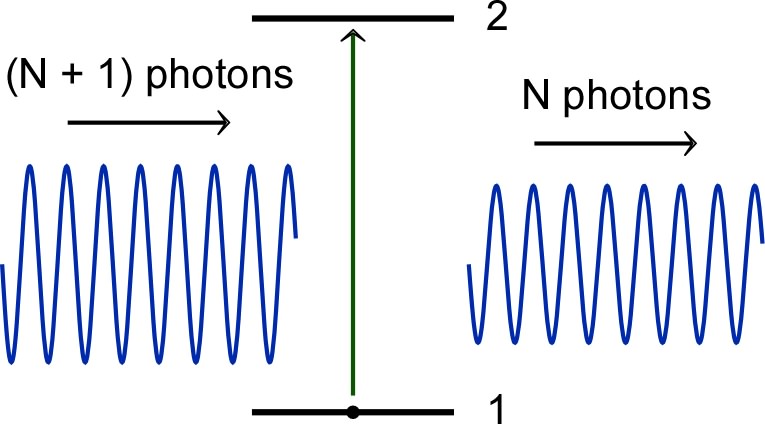

induced absorption removes a photon in the same mode as the outgoing wave (absorption is amplified) ; however, under usual conditions, we do not distinguish the difference between the two kinds of absorption, failing to perceive the reciprocal causality of receptors (associated with the relativistic instantaneousness)